By Tara Saldanha

Abstract

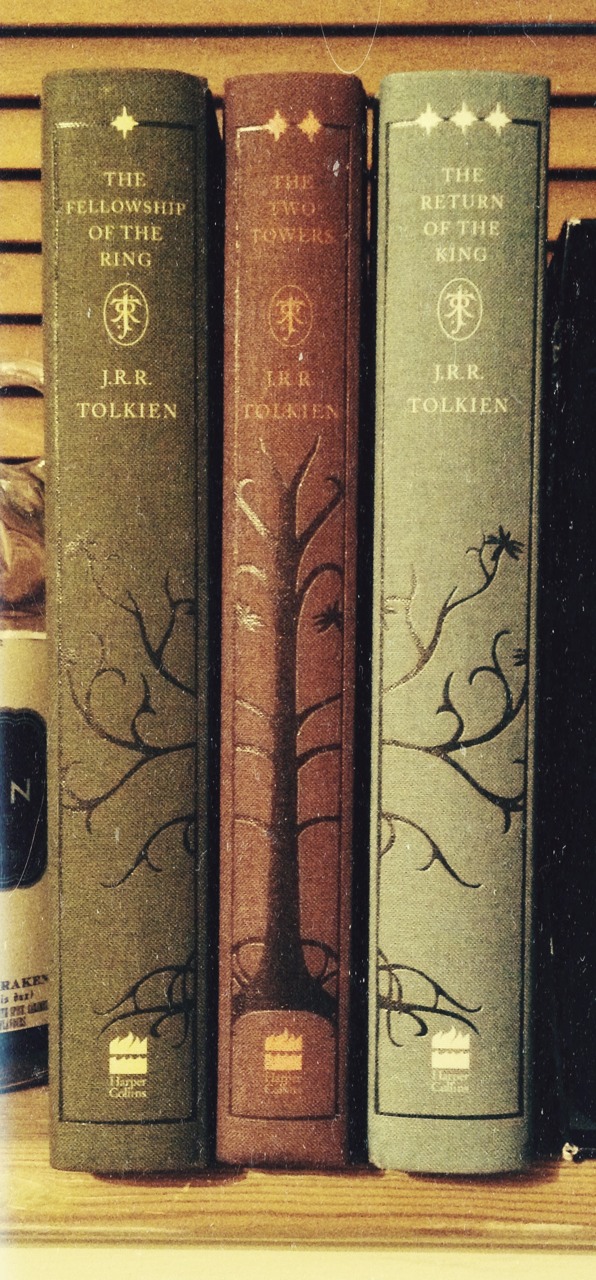

In this paper I will explore J.R.R.Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy to study the effect of the war on fantasy writing. This study will help enrich our understanding of the consciousness of the early 20th century, with regards to the upheaval that war brought. I will also examine the conception of the hero evident in this piece of writing. An enquiry into whether this work can be considered an adequate alternative to Arthurian legend with regard to its incorporation of the post- War consciousness and the alternative conception of the hero will be the last point of interest. I will use The Lord of the Rings trilogy in order to explore this theme. I will also refer to other works by Tolkien, in order to illustrate the three broad areas of study.

Keywords: War, Hero, Heroic Legend, Tolkien, Lord of the Rings

*

J.R.R. Tolkien’s fictional world of Middle-Earth and its histories developed primarily out of a desire to situate language at the center of a particular tale. However Tolkein was quick to reinforce that though the histories and events of his stories were fictional, the place that they were played out in is ‘middel-erd, an ancient name for… the abiding place of Men, the objectively real world.’ (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 257). Thus it wouldn’t be wrong to assume that elements of early 20th century life especially the Great War and changing notions of heroism, humanity and evil made its way into his work. In the course of this eclectic creation it is possible that Tolkein developed a new legendary tradition, one based on new motivations and fears about the present.

Most evident to all but the most casual reader is the over whelming presence of a sense of foreboding in The Lord of the Rings (referring here and throughout, unless otherwise stated, to all three books) from the very beginning. As soon as Frodo leaves the Shire the Nazgul are after him. This all pervasive fear and evil is a result of the totalitarian power that Sauron, also known as the Dark Lord wields. As his power builds he is able to set his minions in motion to track down the One Ring, now in Frodo’s possession. Frodo must destroy the Ring so that Sauron cannot gain possession of it and make his dominion complete. Totalitarian governments and hegemonic powers had begun to rise in the early 20th CY and by 1949 when the last installment of the trilogy had been completed the world had witnessed the horrors of Fascism. Tolkein reiterates in his letter to M. Waldman that evil power in his works manifests itself in the ‘desire for Power’ of the ‘sub-creator’ (or human beings). The desire for power was in order to claim dominion over the rest of creation (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 168). Tolkein goes on to elaborate that this desire for total domination is carried out through certain external creations designed to bend and break individual will. Interestingly Tolkein refers to this in the same letter as ‘the Machine’. In The Lord of the Rings these instruments of domination include malignant weapons forged in the depths of the earth by the Uruk-hai. The Uruk-hai themselves were made in the mockery of elves by the Evil one as a sort of mutant super soldier. (Tolkein 486). Tolkein describes ‘oliphaunts’- lumbering, tank-like beasts that could lay waste to everything in their path being used in various battles. The screams of the Ringwraiths are described as ‘a rending screech, shivering, rising swiftly to a piercing pitch beyond the range of hearing’ reminiscent of the sound of falling shells during wartime. (Tolkein 706) In a letter to his son, Tolkein remarks how during the ‘first war of the Machines’ the soldiers were left maimed or dead and the only one thing triumphant was the Machines (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 124).

It is hard not to constantly see how war affected The Lord of the Rings besides the obvious presence of weaponry. Tolkein referred to war as an ‘animal horror’ to his son in one of his letters (Garth). The book talks of the siege and battle at Helm’s Deep and the war of the Pelennor fields. The fall of Gandalf, who Tolkien described as a guardian angel figure in his Letters, in the mines of Moria could signify the crumbling nature of faith and religion during the 20th century (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 176). The coming together of the Elves and the dwarfs against the common evil despite their mutual animosity is reflective of rival Allied powers collaborating during the two World Wars. Tolkein himself lost several close friends in the fighting. The Dead Marches with their floating corpses and eerie lights are said to be a tribute to the fallen soldiers (Beyond the Movie:The Lord of the Rings). In the telling of the history of the Ents, tree-like rational creatures, and the destruction of their home and loss of the Ent-wives, Tolkein touches upon the destruction of the environment because of warfare and exploitation of natural resources.

During the Second Age of Middle- Earth Tolkein speaks of how the ‘destruction of the…visible incarnation of evil’ was carried out (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 175). However in The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, both set during the third age, evil is unseen, pervasive, occupying the very hearts and minds of the various characters rather than a physical external presence. This raises the question of who then is the enemy in war, probably a question that Tolkein wanted to raise considering the seemingly wholesale loss of humanity during the World Wars.

On the whole it seems to be that the zeitgeist of the early 20th century, especially with regard to warfare and atrocities ensuing from it did indeed influence plot and characterization of The Lord of the Rings in very significant ways. The entire history of Middle Earth emerges as a result of fights for power and domination. The high tales of the early ages are usually written from an elvish standpoint, but War of the Ring and the events that surround it are written from the point of view of a hobbit, as he himself said in one of his letters (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 168). Thus even though Tolkein was adamant that his story was not autobiographical, it seems to depict war as men like him had seen it.

Tolkein’s two most popular works, The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, are both journeys in which the characters must battle with a quest. The players in each of these are a varied bunch. However Tolkein’s heroes are not the archer elves or the dwarfs, skilled in the making and wielding of weapons. Rather Tolkein himself referred to the hobbits as his heroes. In this paper I am not going to attempt which individual may be considered a hero, merely the new expectations of a hero and how these changed possibly due to the world wars. Also, though Tolkien’s heroes are mainly male in keeping with the 20th century model of the hero, I will not be doing an examination of the gender angle to the hero question. Suffice to say that while strong independent female characters do exist, there are only three shown in active roles- their presence is scarce throughout the novel.

Tolkein chooses the otherwise neglected as his hero. From the very beginning the Ring chose Bilbo and was then passed onto Frodo, both hobbits. The hobbits are fairly parochial creatures, sticking to the Shire, never venturing beyond what they know. Tolkein makes them small, diminutive creatures precisely ‘to exhibit the pettiness of man…’ (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 176). Perhaps Tolkein viewed the ongoing political struggles as petty political games being drawn out into battles from which no one would really gain. His hobbit heroes personify this small-minded, selfishness of humans. But the hobbits also provide a model for what humans ought to be. In the same letter to M. Waldman Tolkein goes on to describe hobbits thus, “ They are entirely without non-human powers, but are represented as being more in touch with ‘nature’… and abnormally, for humans, free from ambition or greed of wealth” (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 176). Tolkein strikes down the hero as needing to be a super soldier, with advanced weaponry, and uphold the hero who is in contact with the world around him and able to overcome selfish desires for power.

In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo constantly struggles with the temptation to wear the Ring and so claim supernatural powers, but in the end he is able to defeat his enemy and destroy the source of power. Gollum and to an extent Boromir are presented as foils to Frodo’s character. Boromir represents the fallen hero who gives into to hubris, tries to trick Frodo and gain the ring for himself, but then realizes his mistake and seemingly sacrifices himself to save his friends. Gollum on the other hand is so consumed by desire for the Ring that his very appearance has changed. Unlike Frodo though, he is consumed by his lust for power and dies with the Ring. Jane Chance states that ‘the hero must realize that he can become a monster’ (Chance 162). She goes on to say that it not merely external threats that besiege Tolkien’s heroes but great emphasis is placed on internal threats as well, as mentioned above.

Tolkein however upholds loyalty as the primary trait of the hero. He often claimed that Samwise Gamgee was his true hero. He saw him as the ordinary soldier, a gardener’s son, thrust into a great game. For Tolkein, Sam represents all the loyal ‘privates and batmen’ that went to war (Carpenter 89). Here again we see Tolkein upholding not the commanders of armies and generals as heroes but rather the ordinary foot soldier.

Tolkein states in his letter to Waldman that he had a ‘basic passion…for heroic legend’ (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 167). He commented most particularly on how the Arthurian legends were connected with the land but not with the language of Britain. As a linguist Tolkien’s passion was language and he wanted to create a world that incorporated not only his made-up languages but also one which could be called a wholly English legend, spatially as well as linguistically. Thus the landscape of Middle-Earth as well as its population bears a resemblance to Britain and it is redolent of a Celtic heritage (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 168).

According to Mark Hall, Tolkein makes use of Arthurian elements ‘infused with new meaning and purpose’ (Hall 2). I will explore what exactly this purpose was especially with regard to the political climate in which Tolkein was writing.

In the legends surrounding Arthur, his rising to the status of hero seems to be predestined. Once the sword is pulled from the stone he has no choice but to accept his mantle as the new king. On the other hand both Frodo and his predecessor Bilbo are allowed to choose to embark on their respective quests. Though it is repeatedly stated that the Ring chose them, Gandalf allows them both the choice of remaining in the Shire and ignoring their ‘calling’. The conception of the hero in the new legend that Tolkein wishes to propagate is then not one who is sent or chosen but rather one who chooses and through battling with exterior and internal adversaries emerges heroic.

Arthurian legend is rife with magic, wielded by the good and evil alike. In his letters, Tolkein makes it clear that his conception of magic is power that is appropriated- not inherent- in order to dominate. The most telling difference is between Merlin’s and Gandalf’s approach to magic and power. While Merlin in all versions of the legend embraces power, Gandalf realizes the dangers of appropriating power and rejects all external sources of it (Riga 38). This change in the approach to magic, such a key component of most legend can be seen as a result of a realization of how power had been used and corrupted during the 20th century.

Tolkein does however retain some of the tropes of heroic legend. For instance the Knights of the Round Table are paralleled by the Fellowship of the Ring both in equality and loyalty as well as ambition and betrayal. Arthur and Tolkien’s Aragorn are both unknown heirs brought up in secret away from their kingdoms. However, while Arthur regains his throne as a young man merely by pulling a sword from a stone, Aragorn’s reclamation of his throne involves a long, arduous journey. After several years of wandering, a mature and capable man, he fights and wins back his right to govern. Tolkein borrows the element of the broken sword as carrying much meaning and power, the re-firing of both Excalibur and Narsil symbolizing a resurgence of good against evil. In Tolkien’s heroic legend Galadriel is an elvish queen, the most powerful in all of Middle- Earth. But unlike Arthur’s Queen Annoure she is not a seductress but a ruler in her own right. Mark Hall comments also in how while Merlin is represented as being seduced by women and their magic, Gandalf respects and pays obeisance to powerful women like Galadriel instead of fearing them (Hall 5). Also Tolkein presents his heroes as ordinary people who do extraordinary things. They celebrate birthday parties and engage in friendly competition. Also the love represented in Tolkien’s works is not that of chivalric legends where fair princesses marry gallant knights. Here we see that the immortal elvish Arwen agrees to marry the mortal Aragorn even before he has won back his throne. Tolkein makes special mention of how the Hobbit heroes go back and begin ordinary lives in The Shire, marrying, raising families and tending to the their gardens.

Tolkein thus instated a new type of hero. As he wrote to M. Waldman ‘…without the simple and ordinary the noble and heroic is meaningless’ (Tolkein, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein 177). Reflecting the sentiments of war poets like Sassoon and Owen as well as his contemporaries like Auden, Tolkein used his new heroic legends in order to establish the ordinary soldier as the more believable hero.

This can be seen as an attempt to illicit a sense of loyalty to Britain and is supported by a statement made by Tolkein; as seen earlier, he wanted to write a purely British legend. Legends and folklore go a long way in securing a sense of legitimacy of power and overall loyalty to the country. The Arthurian legend that Arthur will return when England is in danger supports this statement. In The Lord of The Rings, when Frodo nears the wastes of Mordor he chances upon a trail of flowers that seem to form a crown on the broken statue of a former king (702). This is interesting because it ties in with Tolkien’s use of a British landscape and aesthetic in his works. In collaboration with this particular instance, it seems to be implied that nature itself gives it’s assent to a particular rule. When viewed in terms of the political struggle for power in the 20th century, we can see how affinity with nature can be used to solidify a certain national rhetoric.

From a post colonial perspective Tolkien’s work seems imperialist. He makes repeated statements about ‘the darkness of the East’ (Tolkein, The Lord of the Rings 703). Mordor, Sauron’s seat of power is itself in the east of Middle-Earth. On the other hand, the Grey Havens, a sort of Elven haven, redolent with culture, art, spirituality and posterity can be reached by going into the West. Tolkein was writing at a time of colonial struggle when Britain was losing control over its colonies having already lost its largest and most lucrative, India, by the time the book was finished. Therefore it is not farfetched to say that a sense of racial superiority pervades his new British legend.

In conclusion, The Lord of the Rings states that all the evil and wild men of the south had fallen under Sauron’s power. Tolkien seems here to be commenting on how the blame for the horrors of the war must be pinned on all of humanity but with emphasis on the ordinary as having potential to be heroic. These new heroes situated within a heroic tradition that upholds national identity and the everyday are evidence of the effects of the 20th century consciousness on the works of J.R.R. Tolkein.

References

“Beyond the Movie:The Lord of the Rings.” 1996. National Geographic. Web. 13 Dec 2015.

Brown, Terrence Neal. “Review: Tolkein and the Great War:The Threshold og Middle-Earth by John Garth.” Religion and Literature 38.4 (Winter 2006): 115-117. Web. 13 December 2015.

Bruckner, D.J.R. “Concerning Hobbits and Phillip Marlowe.” The new York Tmes on the Web 15 Nov 1981: n.p. Web. 9 Feb 2016.

Carpenter, Humphrey. Tolkein: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books, 1977. Print.

Chance, Jane. Tolkein’s Art: A Mythology for England. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 2001. PDF File.

Garth, John. “Battle of the Somme:The ‘Animal Horror’ that Inspired J.R.R. Tolkein.” The Telegraph 4 Oct 2013: n.p. Web. 12 Dec 2015.

Hall, Mark R. “Gandalf & Merlin, Aragorn & Arthus: Tolkein’s Transmogrification of the Arthurian Tradition & its Use as a Palimpsest for The Lord of the Rings.” Inklings Forever 8 (2012): 1-10. PDF File.

Riga, Frank P. “Gandalf & Merlin: J. R.R.’s Adoption and Transformation of a Literary Tradition.” Mythlore 27.1/2 (2008): 38. Print.

Tempest, Deborah. King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Penguin Books Ltd., 2006. PDF File.

Tolkein, J.R.R. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkein. Ed. Humphrey Carpenter. London: George Allen & Unwin, n.d. PDF File.

—. The Hobbit. London: HarperCollins, 1995. Kindle File

—. The Lord of the Rings. London: HarperCollins, 2005. Print.